When I drink, I blackout. It happens quite a bit. And it shouldn't. But something about my brain shuts off if I have a couple drinks and I end up, as my friends say, acting like a "bad kid". I cause mischief. I wrestle and pick people up. I bounce around from conversation to conversation, saying who knows what.

This isn't some not-so-anonymous AA anecdote. This isn't a rant on abstaining from a little wildness here and there, or even from the deliciousness of some guilty pleasures. This is just to recognize the expression that rules our lives: What you put in is what you get out.

I blacked out again a few weeks ago at the company Christmas party. It's fuzzy when I left but what I do know is I rode the subway back and forth all night. The rumble of the tracks put me right to sleep. When I finally found my way back and crumpled into my bed at the almost comical minute of 6:01am, I knew the next few days would not be pleasant for me. Three hours later, I was dragging my ass to work. Never is it more clear that there is no other hangover cure but time than after a blackout.

My brain was a puddle. My muscles ached. And the guilt of the whole situation was a rotten cheery on top.

I don't like being useless. I'd much rather run on jet fuel for twelve hours than glide through the day, or, worse, stumble through the thorns. I want to be awake and ready. And then I prefer to pass out at a reasonable hour to wake up and do it all over again. Am I crazy?

But with what I have to guess was at least six Manhattans and a couple of beers, what else could I expect? My body had been poisoned and now it was recovering.

What we consume transforms everything we express to the world. That's not an understatement. Your gut is covered in neurons and, according to Scientific American, "filled with important neurotransmitters". Some scientists call it "the second brain".

Your body works best when it is fed the best. Of course, you don't need to be a scientist to know devouring a tray of lasagna is no better than chewing on a kale salad. The disconnect often happens with the first brain. What we put in our guts doesn't just sit there with us on the couch, it affects the whole machine. Aubrey Marcus, founder of Onnit Labs, made a good point on The Art of Manliness podcast when he discussed why the brain needs to be maintained regularly. Marcus said, "The brain is actually an organ. As with the muscles or skin or the liver that organ has input that it uses to create the output. Now the output happens to be thoughts and cognition and personality and a lot of other things."

And just as I didn't respect what or how much I was dumping down into my guts, I didn't stop to think how partying with no regard would destroy what I put out to the world over the next couple of days.

Okay, you might be rolling your eyes at this point. "Get over it, Dan, we all get drunk sometimes," you'd say. "You're not a surgeon missing shifts!" Thanks, that's comforting. But this idea goes further. It's not just about what you put in your mouth, it's what you allow into your mind.

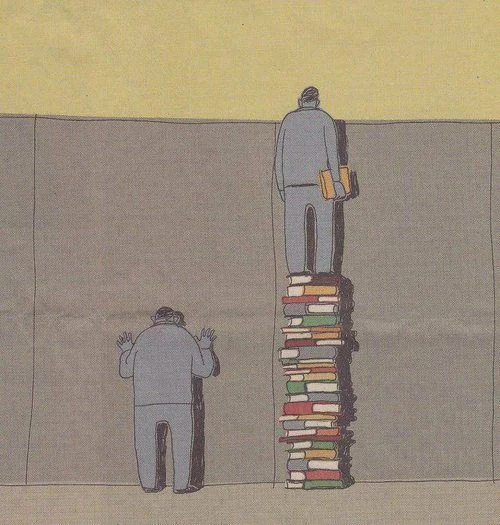

A good idea can transform your life in a second. I don't need to explain how. There are an infinite amount of ways. And books are full of the stuff. They can deliver a heavy slap in the face. Ryan Holiday put it simply in Thought Catalog when he described the secret rules of great readers: "Dollar for dollar there is no better investment in the world than a book." You can't go any further in this world than where you are without learning something and books are there for the picking. What is it? $15? And what if that book holds the key to your Life's Most Difficult Problem? It could even be the worst kind of problem, as Holiday says, "What’s a book that saves your life worth? That’s not hyperbole. We all hear constantly about books that changed people’s lives."

If you're willing to ingest a new idea, it is very well possible that it could change everything that's still before you.

Maria Popova of Brain Pickings does this constantly. She digests an incredible amount of content every day just to make sense of the connections this universe offers through the ideas in books. Recently, she wrote about William J. Reilly's 1949 book, How to Avoid Work, and pulled this appropriate gem: "In a world marked by constant change, where the rich of today are often the poor of tomorrow, due to circumstances beyond their control, the only security is your ability to produce something of value for your fellow man, and your only guarantee of happiness is your joy in producing it."

We're devouring information every day and producing alike. Everything is flowing through us and right down to the smile you shoot your neighbor walking down your apartment steps is part of the exchange. Every second is your chance.

There might even be some science behind this grand exchange. MIT physicist Jeremy England has a new and exciting theory that might even call this value exchange the driver for the origin and evolution of our world. Quanta Magazine reporter Natalie Wolchover explains England's theory starting with the basis that living things capture energy from the environment and "dissipate that energy as heat". That's a given in the field of psychics. England believes to have created a mathematical formula that explains how groups of atoms going through this process "will often gradually restructure itself in order to dissipate increasingly more energy." In England's words, “You start with a random clump of atoms, and if you shine light on it for long enough, it should not be so surprising that you get a plant.”

And if England's interpretation is true, it could mean a great deal to the question of the meaning of human life.

While we can leave the heavy lifting to the scientists here, what it all boils down to is something more coherent and more complex. We are making the decisions that both consume and produce our environment. Shots of Awe creator Jason Silva explains this exchange through the concept of ontological design, or the process of our creations creating us here and vice-versa. Silva wonders about our world as a meaning-making circle. We have to question: what came first, the person or the idea? And does it even matter?

What we're left with is our decisions. Whether you believe in fate or free will, it's amazing just to pull back and see how it all collides together. And if I think hard enough, in some twisted way, my blackout subway adventure might have done some good. My coworkers got some good belly laughs out of it, and the story helped me start the ideas in this entry. There is always something of value to everything we consume, we just need to find out if it's worth it to our world.